Hydrography

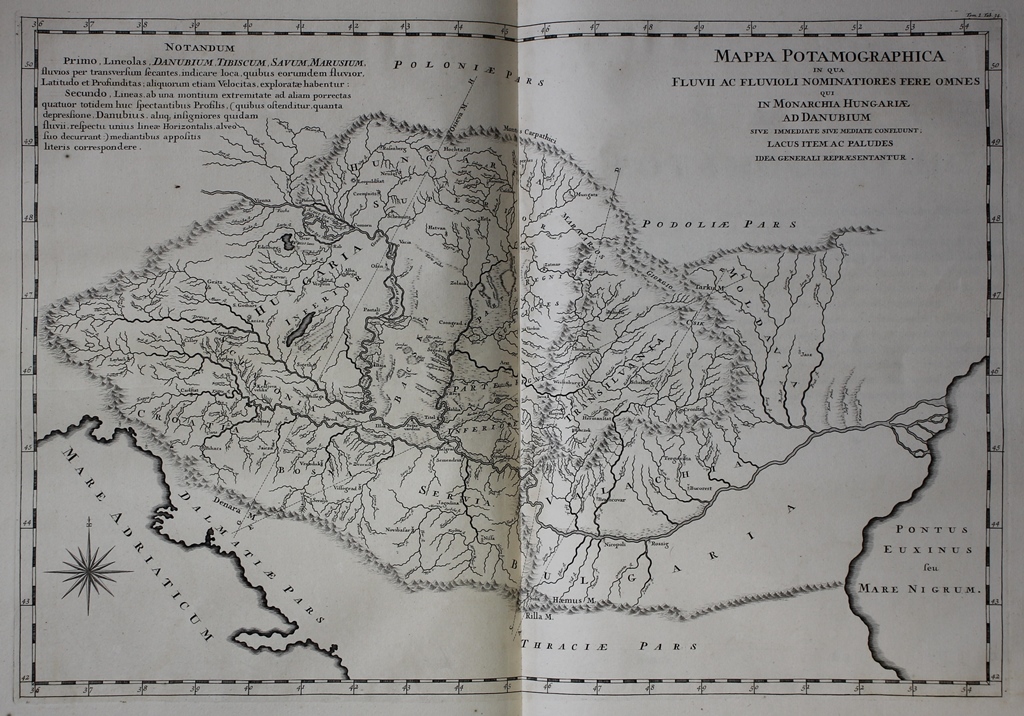

The third and final part of the first volume of Danubius Pannonico-Mysicus is concerned with the hydrography of the Danube, while the results of various hydrographical measurements and experiments are also recorded in the sixth volume of miscellaneous material.[1] The hydrography section begins with a thematic hydrographic map, the ‘Mappa Potamographica’, of the Pannonian Basin, also known as the Carpathian Basin, showing almost every major river and their tributaries that flow into the Danube as well as the lakes and swamps in the region.[2]

Luigi Ferdinando Marsili, Danubius Pannonico-Mysicus: Observationibus Geographicis, Astronomicis, Hydrographicis, Historicis, Physicis (The Hague & Amsterdam, 1726), i, Plate 34. Hydrographical map (Mappa potamographica) of the Pannonian Basin.

Cross-sections of the Pannonian Basin along four straight lines shown on the ‘Mappa Potamographica’, labelled A-B, C-D, E-F and G-H, are illustrated on a separate plate in order to depict the relative altitudes, measured by a barometer, of the mountains, valleys and rivers traversed by these lines. Marsili goes on to list the major rivers flowing into the Danube, dividing them into groups II, III, and IV according to their size and provides details such as their source area, mouth and length. He includes several illustrations and cross-sections of the Danube to show the structure and composition of the river’s bed and banks. The widths and depths of the Danube measured at eight different locations, for instance, are depicted on a double-page plate of cross sections along with those of the Sava river at two locations and the Tisza and Maros rivers at one location each.[3]

Marsili hypothesised that there were subterranean channels connecting individual bodies of water (rivers, swamps and lakes) based on observations he had made. He cites the Danube-Tisza interfluve, which is a strip of elevated terrain between the Danube and Tisza river valleys where the Tisza runs parallel to the Danube at a higher altitude, as an example of where such channels exist. Marsili theorised, based on what he observed in the summer of 1693, that floodwater from the Tisza flowed eastwards underground towards the Danube because there was flooding in the low-lying fields of the interfluve in the Bačka region at a time when there was very little water in the Danube and its swamps.[4] He writes that rivers feed water into swamps through channels that are known in Hungarian as foks and that swamps also feed water into rivers. He gives an example of the former by recalling an occasion when he received an alert from Vienna that the Danube was flooded in July 1694 and that he should expect the floodwater to reach where he was stationed downstream imminently. No such flooding occurred, however, because, as he explains, the swamps between Vienna and his location had to be filled by the floodwater beforehand.[5]

Luigi Ferdinando Marsili, Danubius Pannonico-Mysicus: Observationibus Geographicis, Astronomicis, Hydrographicis, Historicis, Physicis (The Hague & Amsterdam, 1726), vi, Plate 3. Map of Donaueschingen.

Volume VI begins with four plates of maps and cross sections relating to the sources of the Danube river as well as a map of the sources of the streams, predominately in Swiss territory, that feed the Rhine river. Marsili had an opportunity to study the sources of the Danube before the onset of winter in 1702 while he was resting at Elzach on the Ilz river in southwest Germany following his inspections of and improvements to the defences of the Rhineland and Black Forest during the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-15) and prior to him taking up the post of second in command of Breisach Castle on the banks of the Rhine river in December of that year.[6] Elzach was not far from Donaueschingen where the source of the Danube was traditionally thought to be a spring on the estate of the Fürstenberg princely family.[7] The short Donaubach river flowed from this spring and joined the Brigach river, which is the shorter of the two headstreams, the other being the Breg river, that converge at Donaueschingen to become the Danube river. Marsili, along with a secretary and draughtsman, travelled to Donaueschingen to survey the watercourses by drawing sketches and taking readings with a barometer to measure heights.[8] He concluded that the source of the Breg river, six kilometres northwest of Furtwangen im Schwarzwald, was the true source of the Danube because it’s spring was at the highest altitude above sea level.[9]

Luigi Ferdinando Marsili, Danubius Pannonico-Mysicus: Observationibus Geographicis, Astronomicis, Hydrographicis, Historicis, Physicis (The Hague & Amsterdam, 1726), vi, p. 25. Experiments to measure the velocity of the waters of the Danube river.

Marsili measured the velocity of the water at different depths near the surface, middle and riverbed on the Danube and Tisza rivers by suspending a lead ball from a plumb line attached to a quadrant that was fixed to the side of a boat. He calculated the speed of the current at the different depths from the angle that the line made on the quadrant.[10] Domenico Guglielmini (1655-1710), professor of mathematics and hydrometrics at the University of Bologna who would later publish a treatise on the nature of rivers entitled Della natura de’ fiumi, trattato fisico-mathematico (Bologna, 1697), exchanged letters with Marsili instructing him on how to measure the velocity of water using this method.[11] The quadrant and ball used by Marsili produced unreliable measurements, however, because the plumb line was pulled by the current in deep fast moving water and the angle it made on the quadrant did not indicate the correct location of the lead ball suspended by the line.[12] Marsili tabulated the results of his measurements along with the depths and the locations he took them, with the table above showing the measurements that he took at sixteen equally spaced points across the width of the Danube at the bridge in Petrovaradin in Serbia.[13] The measurements recorded on the river Tisza at Žabalj and the bridge near Bečej, both in Serbia, appear on two separate tables.

Marsili also examined the properties of flowing river waters, stagnant marsh waters, water from wells, mineral waters, waters from rain and hail, and thermal spring waters using various chemicals and he weighted the different waters with a hydrostatic balance. He tabulated the results, along with the locations of where he took the samples, in charts spread across five double-page plates.[14]

Luigi Ferdinando Marsili, Danubius Pannonico-Mysicus: Observationibus Geographicis, Astronomicis, Hydrographicis, Historicis, Physicis (The Hague & Amsterdam, 1726), i, Plate 41. An explanation as to why marshes are commonly formed by rivers.

TEXT: Mr Antoine Mac Gaoithín, Library Assistant at the Edward Worth Library.

SOURCES

Deák, Antal András (ed.), A Duna Fölfedezése. Luigi Ferdinando Marsigli, Danubius Pannonico-Mysicus. Tomus I, A Duna Magyarországi és Szerbiai Szakasza = The Discovery of the Danube. Luigi Ferdinando Marsigli, Danubius Pannonico-Mysicus. Volume I, The Hungarian and Serbian Section of the Danube (Budapest, 2004).

Deák, Antal András, Maps from under the shadow of the crescent moon = Térképek a félhold árnyékából = Carte geografiche dall’ombra della mezzaluna = Landkarten aus dem Schatten des Halbmondes (Esztergom, Hungary, 2006).

Deák, Antal András, ‘Marsigli, Luigi Ferdinando’, in Matthew H. Edney & Mary Sponberg Pedley (eds), The History of Cartography. Volume 4, Cartography in the European Enlightenment (Chicago & London, 2019), pp 920-922.

Deák, Antal András, ‘Müller, Johann Christoph’, in Matthew H. Edney & Mary Sponberg Pedley (eds), The History of Cartography. Volume 4, Cartography in the European Enlightenment (Chicago & London, 2019), pp 1019-1020.

Stoye, John, Marsigli’s Europe, 1680-1730 : the life and times of Luigi Ferdinando Marsigli, soldier and virtuoso (New Haven & London, 1994).

[1] Volume I of the Danubius Pannonico-Mysicus concludes with a plate with illustrations of the thermal Baths of Buda in Buda Castle that were sketched by Marsili following the Siege of Buda in 1686, which is reproduced on the ‘Contact Us‘ webpage.

[2] Deák, Antal András (ed.), A Duna Fölfedezése. Luigi Ferdinando Marsigli, Danubius Pannonico-Mysicus. Tomus I, A Duna Magyarországi és Szerbiai Szakasza = The Discovery of the Danube. Luigi Ferdinando Marsigli, Danubius Pannonico-Mysicus. Volume I, The Hungarian and Serbian Section of the Danube (Budapest, 2004), p. 143.

[3] Ibid., pp 143-144.

[4] Ibid., p. 144.

[5] Ibid., p. 145.

[6] Stoye, John, Marsigli’s Europe, 1680-1730 : the life and times of Luigi Ferdinando Marsigli, soldier and virtuoso (New Haven & London, 1994), pp 228-230.

[7] Deák, The Discovery of the Danube, p. 153.

[8] Deák, The Discovery of the Danube, p. 153; Stoye, Marsigli’s Europe, 1680-1730, p. 228.

[9] Deák, The Discovery of the Danube, p. 153.

[10] Deák, The Discovery of the Danube, pp 118, 153-154; Stoye, Marsigli’s Europe, 1680-1730, p. 126.

[11] Deák, The Discovery of the Danube, p. 118; Stoye, Marsigli’s Europe, 1680-1730, p. 148.

[12] Deák, The Discovery of the Danube, pp 153-154.

[13] Deák, The Discovery of the Danube, p. 118; Stoye, Marsigli’s Europe, 1680-1730, p. 126.

[14] Deák, The Discovery of the Danube, p. 154; Stoye, Marsigli’s Europe, 1680-1730, p. 126.